What is Attention Really For?

Sophisticated people can sometimes make it seem that the issue of attention is very complicated. But in truth, the logic of attention is pretty simple. And understanding the simplicity of attention in general can help us understand the simplicity of a specific use case: attention to ads.

The complicators have a point: attention studies is a highly contested space. Is it best to understand attention as a top-down process, which helps us hunt out things of meaning or significance? Or is it better to think of it as a bottom-up system, where meaning emerges from what the world presents us?

Is attention automatic (like when we turn our heads at the sound of a loud bang) or directed (like when we listen to discern the bassline of a song)? Should we think of attention as a filter, that helps us sift through the noise to find the meaning in the world? Or is it more like a spotlight, roving over the world in search of significance? Is attention a commodity that gets used up, or a process that uses things up?

These are complicated questions: like I said, the complicators have a point.

But perhaps there is a way of cutting through this particular Gordian Knot, and that is to ask: what is attention for? What is its purpose — for any animal, but especially for a mid-sized ape like ourselves, who is sometimes a predator and sometimes prey?

The answer to that question is easy: attention is for keeping us alive.

Prof. Wayne Wu’s uncompromisingly titled Attention (2013) defines attention as ‘selection for action’. As creatures, we have aims and purposes in the world, one of which is staying alive in the face of unexpected events. We therefore need a system that is flexible enough to help us act in the world, while also avoiding being acted upon. This is the job of attention.

This is not an easy task, especially when you remember that the world is very big, full of opportunities and dangers, and our heads are, by comparison, very small. How can our limited brains take in all the information from an essentially limitless world to act within it?

The truth is that we don’t. We guess. Our perceptions, as attention researcher Richard Gregory famously put it, are hypotheses. We are presented with a scene, which we proceed to ‘make sense of’ in terms of our aims and purposes. If our initial guess is challenged by additional data, then we will invest more attention to make a newer, better sense of the situation. That little black object in the sky is probably a bird — things up there that move like that usually are. But wait, there’s a rumbling noise at the same time. We look again: no, it’s a plane. And unless we’re plane-spotters, that’s probably where we will leave it.

But if we are plane-spotters, that’s when we invest even more attentional resources to determine the make and model, until even the nerdiest observer is satisfied, and turns their attention elsewhere. This process of deploying attention to generate successive ‘drafts’ of reality based on our aims and objectives in the world is well described in Jakob Howhy’s The Predictive Mind (2013).

Understanding how attention works in general can help us understand how it works in the specific case of advertising. If we can agree that the essence of advertising is attracting attention, then what does the attention data tell us?

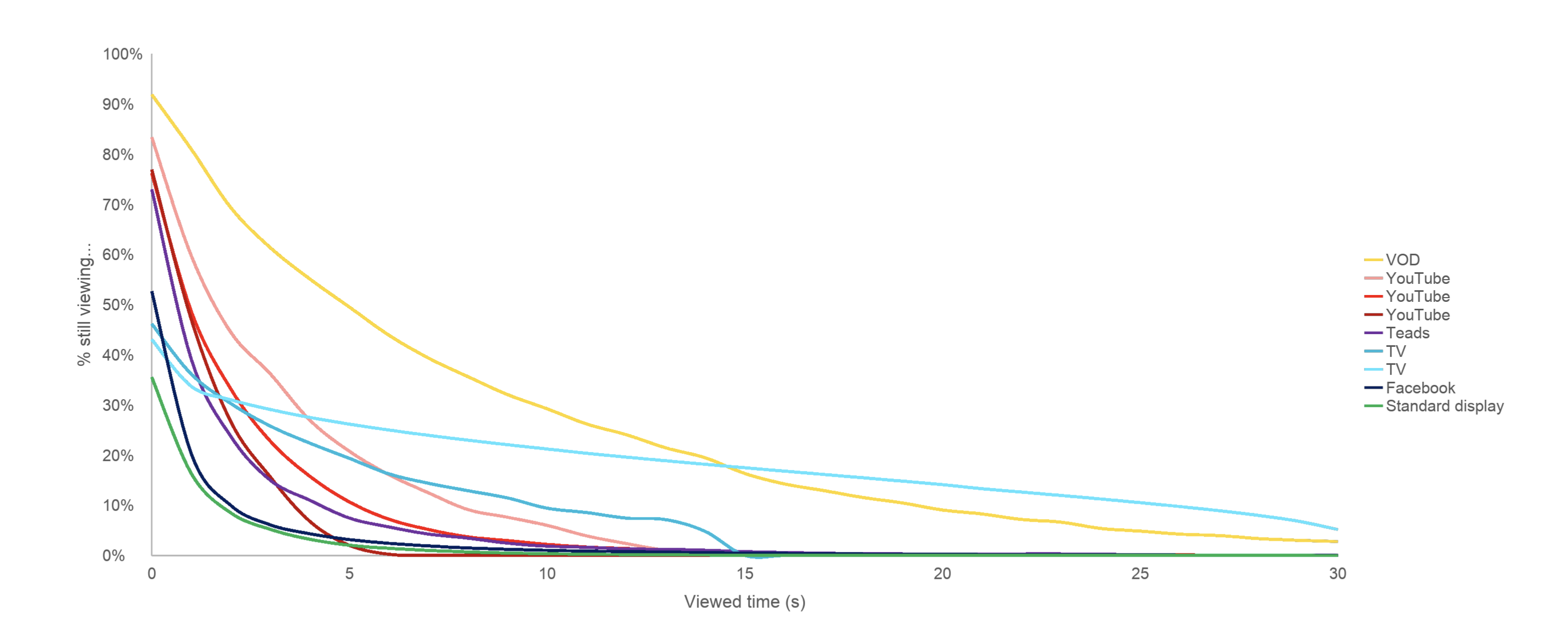

A single chart looking at the distribution of attention to ads in different media (courtesy of Lumen and TVision) throws up three important points:

1. Selection for rejection.

If ads get looked at at all (and that is a big if) most of them get looked at for a very short amount of time. In some cases, only 10 or 15% of ads in a particular medium get even one or two seconds of visual engagement.

This suggests that, in many cases, the action people are taking when they elect to view an ad is rejection. Oh, it’s an ad, nothing to see here. People are guessing that they don’t have to invest any more attention in the ad: it’s up to your creative to make it worth their while.

2. Mere exposure.

We know that even these small levels of attention can have a positive impact on memory, intention to purchase and actual sales.

But we should remember what type of impact it will be having. This is the merest of mere exposures, with images and associations logged away for future recall rather than immediate, considered action.

3. Beware the occasional weirdo.

In all cases, however, there are instances when people have deeply engaged with ads — for instance, about 9% of TV ads get watched right the way through.

It could be that these are instances of amazingly engaging creative or perfect targeting that has, for once, delivered the right message to the right person at the right time — like our plane-spotter example.

But how representative of the norm is this? Should we be making ads for these engaged edge cases, or should we be designing for the distracted majority?

Attention science tells us that attention is for selection for action: it’s about keeping us alive, helping us achieve our aims and purposes in this world.

When you put advertising in this context, we can get a better handle on who’s in charge when it comes to attention to ads. The advertiser can propose, but it is the reader who disposes their attention — and the customer is always right.