We Need to Talk About the Carbon Cost of Attention

It’s hot. It’s too damn hot. It’s so hot that villages on the outskirts of London are burning up in wildfires. It’s so hot that even climate change sceptics like Professor Byron Sharp might be changing (or re-changing) their mind about the reality of climate collapse. It affects us all; we’re all implicated, and it’s all of our responsibilities to do something about it.

The advertising industry is definitely part of the problem, but we can also definitely be part of the solution. And if we are clever, the solution we come up with may be better than what went before.

The first thing to do is admit that advertising is contributing to the climate crisis. I don’t mean that we’re responsible to creating unsustainable demand: our tardy, apish industry is better at directing—rather than manufacturing—desire. What I mean is that advertising itself produces a lot of CO₂—in our offices, in our production practices, and crucially in our media buying.

The carbon cost of media buying is a novel idea, but pretty obvious when you think about it. As the good people at Scope3 have begun to point out, digital advertising is a significant polluter in itself: millions of phones receiving billions of ads after trillions of ad auctions every day use up a lot of electricity, which, in turn, requires a lot of carbon dioxide to be pumped into the air.

What’s especially tragic is that when the ads finally reach our devices we often ignore them. We incur a definite (carbon) cost but only achieve a potential attention gain. Lumen’s eye-tracking research has shown that, for some formats, as few as 9% of impressions that reach the screen end up being looked at. All that energy for so little engagement.

But there is hope. Not all ads get ignored: different formats, publishers, and platforms are much better or worse at turning the opportunity to see an ad into actual viewing. When this ‘attentive seconds per thousand’ data is combined with ‘cost per thousand’ numbers, buyers can distinguish the true ‘cost per thousand seconds of attention’ between media alternatives.

And this in turn can be linked to the carbon cost of the media employed, to create a new and potentially powerful means of assessing media: the ‘carbon cost of attention’.

Lumen has been working with Scope3 and Havas to bring this concept to life, launching our ‘carbon cost of attention’ tool at Cannes Lions earlier in the summer. We combine Lumen’s impression-based attention predictions with Scope3’s carbon cost predictions and the pricing information available to a major trading desk like Havas to understand the true financial and ecological cost of the attention that we’re buying as an industry.

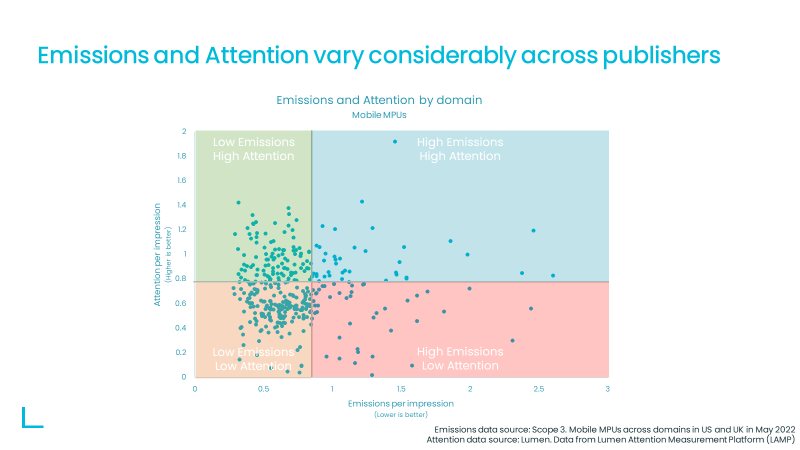

Already, we are seeing considerable differences for ads of the same format across publishers:

In the bottom left-hand quadrant of the chart above, we have low attention/low emissions publishers: a sad state of affairs, but not a disaster for the advertiser or the planet. What we want to avoid is shown to the right, an ‘attention desert’: low attention, but high emissions, which is the worst of all worlds. Instead, we should aim for publishers who provide high attention with low emissions: an advertising ‘Garden of Eden’.

What puts some publishers in the ‘carbon cost of attention’ good books, and others on the naughty step? Well, there are a number of factors, but some of the biggest include:

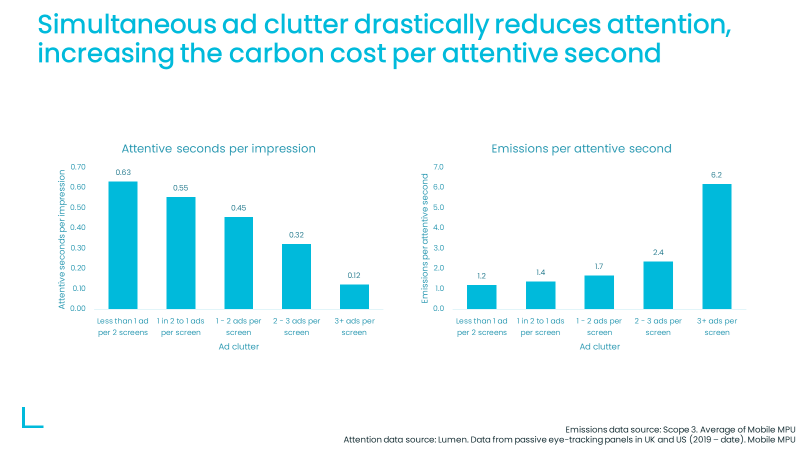

1. Clutter: as the chart below shows, the more ads that are served simultaneously on a screen, the less attention each receives. Given that the carbon cost for each ad stays the same, the ‘carbon cost of attention’ therefore skyrockets on cluttered pages.

It’s as if people can’t see the wood for the trees. This is bad for the advertiser (because people aren’t attending to their message), bad for the reader (as they often feel overwhelmed by ads), and, in a bitter irony, bad for the trees.

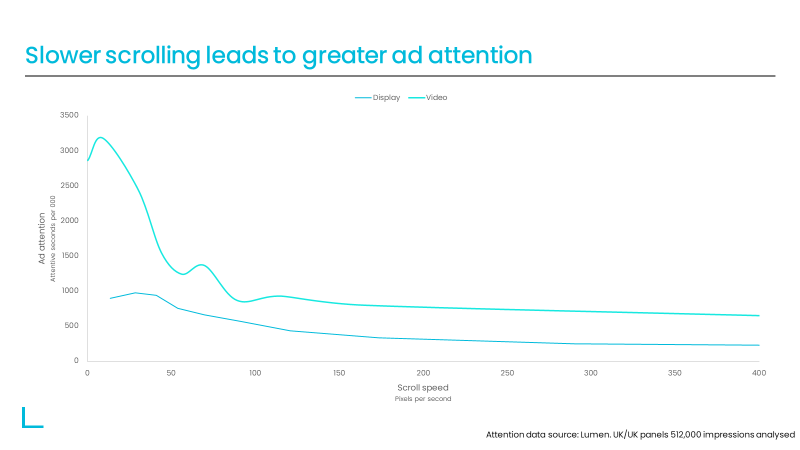

2. Scroll velocity: the slower people scroll the page, the more attention they give to the accompanying advertising.

Again working with Havas, and this time in partnership with Teads on the Project Trinity report, Lumen has found that attention to advertising is in part a function of how slowly people read a page. This in turn has a knock-on effect on the carbon cost of attention: ‘slow media’ leads to ‘sustainable attention’.

3. Streaming video: video advertising tends to get significantly more attention than static display advertising. But downloading a video to your phone can be fearsomely energy intensive, the increased carbon emissions outweighing the increased attention performance.

This is what is so exciting about streaming video services such as SeenThis, which allow advertisers to achieve all the attention benefits of video advertising at a fraction of the carbon cost.

***

We have become used to talking about an ‘attention economy’ – the cost of attention and the value of attention are well now established concepts.

But perhaps we should think more of the ecology of attention: one that safeguards the interests of advertisers, publishers, consumers, and the planet.