People Do Watch Ads… Just Not in the Way You Think

Many advertisers labour under the delusion that consumers see all their ads and watch them all the way through.

This is nonsense.

No one has to watch your bloody ads – and frequently they don’t.

Yet we make ads as if people want to look, we buy ads as if they have to look, and we measure ads as if they must have looked. As a result, our creative development is often weak, our media-buying is often poor, and our attribution models are frequently meaningless.

If only we understood the world as it is, rather than as we would want it to be, we could make better creative, plan better media and measure reality rather than supposition.

Because advertising does work – it just works in a slightly different way to the way we want it to work.

The first thing to acknowledge is that, as advertisers, we can’t always get what we want. People are very good at ignoring our ads, and when they do look, they don’t always watch right the way through to the ‘reason to believe’, or tag line.

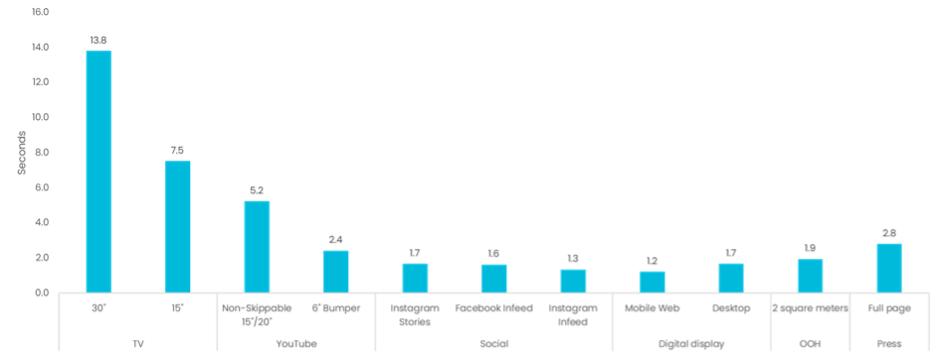

One of Lumen’s most famous charts (which combines our attention data for digital, OOH and print with TVision’s comparable data for TV) outlines the average time people spend looking at ads in different media:

A 30-second TV ad gets a lot more attention than many other media – but it doesn’t get a full 30.

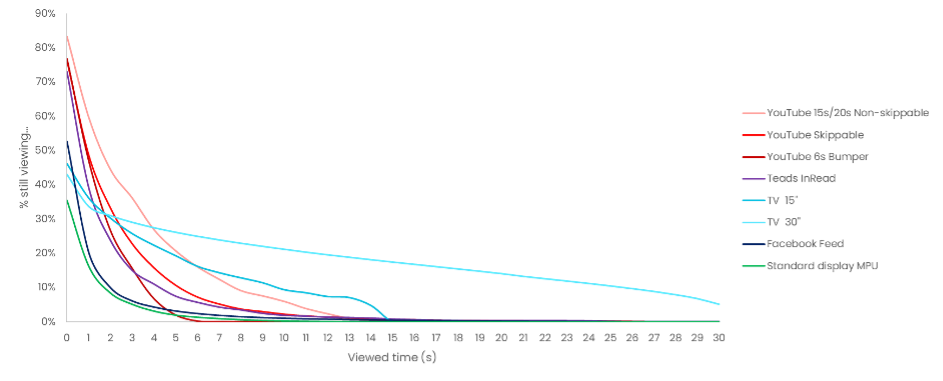

Averages can hide as much as they reveal, so with a bit more digging, you can see the distribution of attention across media. This is even more revealing. It shows that, for most media, most people will look at some of the ad, but very few will watch for the full duration.

Reducing the number of media on the chart for clarity, we can see that most digital video formats get some attention, but this attention is rarely sustained. It also shows that while TV ads might not always be looked at – people go out of the room to make a cup of tea, or stare at their phone until the ads are over – at least some get watched for a full 30 seconds.

A chart like this might lead you to think that the trick is to put all your branding in the first couple of seconds, because that’s what people watch. Not so fast. What this chart tells you is the total number of seconds different proportions of people watched the ad for. But are these seconds at the beginning or the middle or the end of the ad?

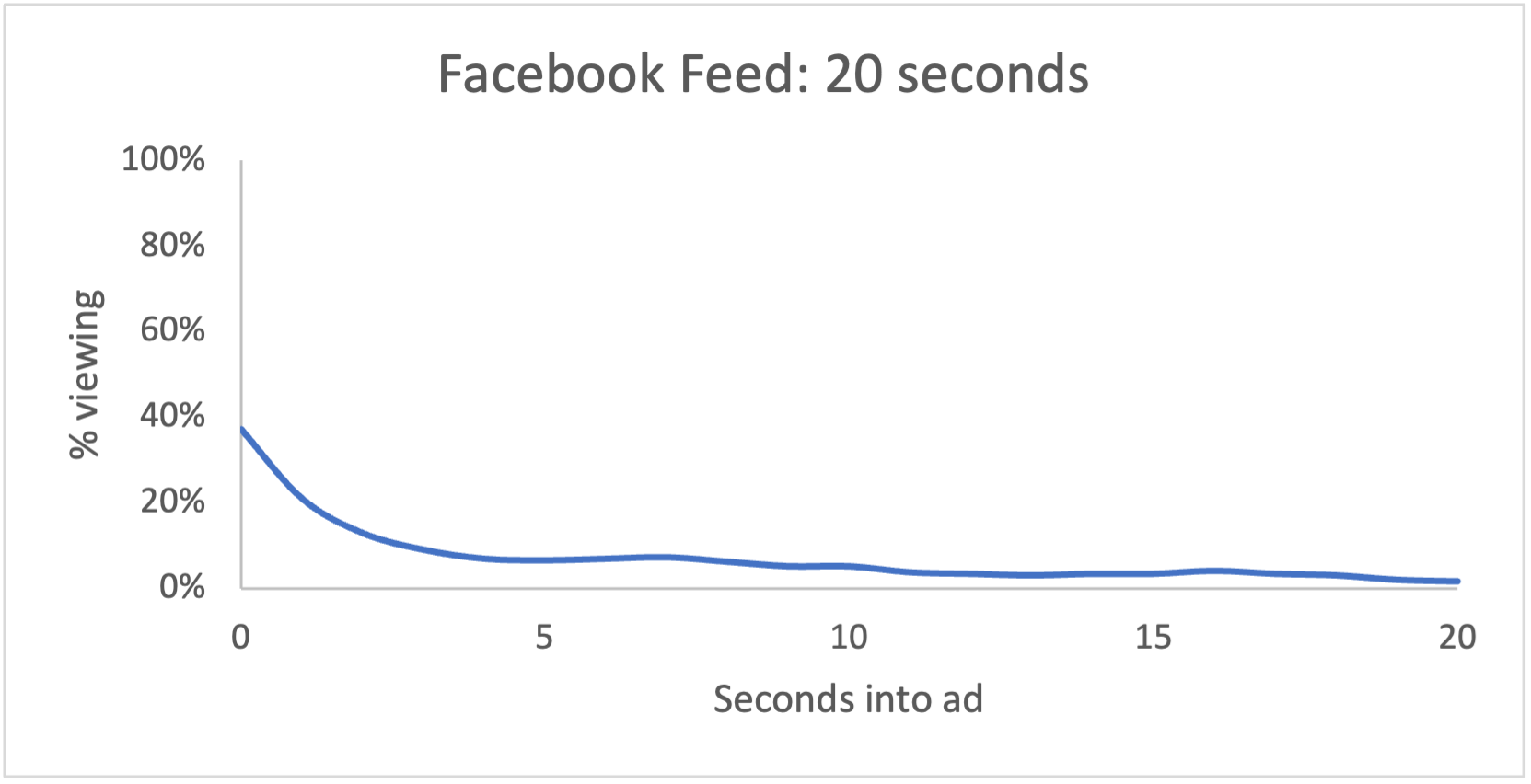

Further analysis reveals the lived experience of engaging with ads across media. Let’s simplify things even further and just compare 30” TV, YouTube, and 20” in-feed video for Facebook.

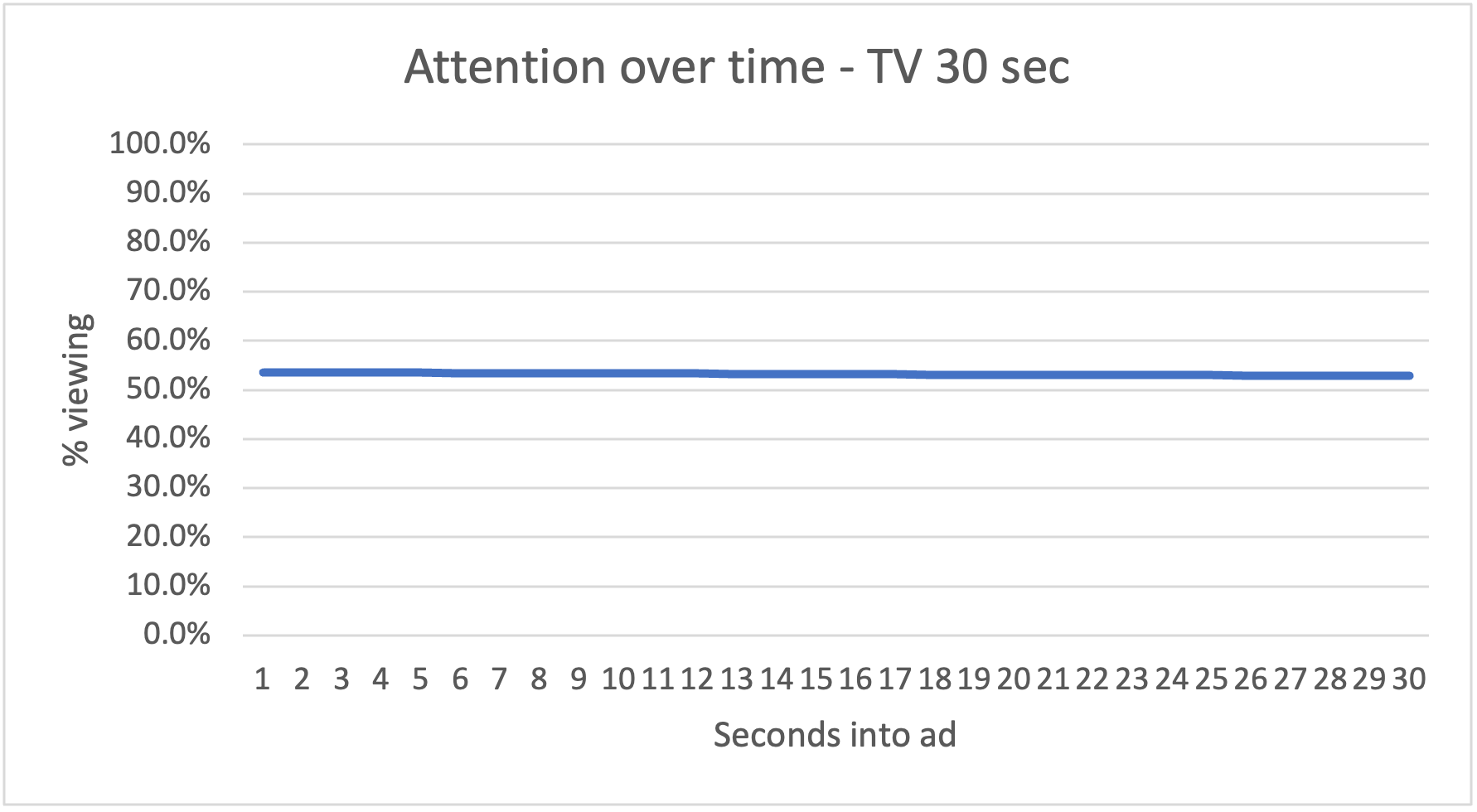

Looking at attention over time for TV ads (the data is supplied by TVision once again), we see that, at any one time, about 53% of people are watching an ad, and that this is pretty stable over the length of the average ad.

This suggests that people are looking up from their phones, clocking what’s on the TV screen, and then looking back at their phones again and across the hundreds of thousands of ads in the TVision database, and this is done in a dependably random fashion.

Some creative will get more attention than the average. Some ads might get more attention at the beginning and peter out towards the end, whereas the reverse will be true for others. Some ads might get more attention when they are first aired and progressively less and less as frequency builds. But, in general, when you are buying TV ads, you’re getting a large number of slightly distracted viewers.

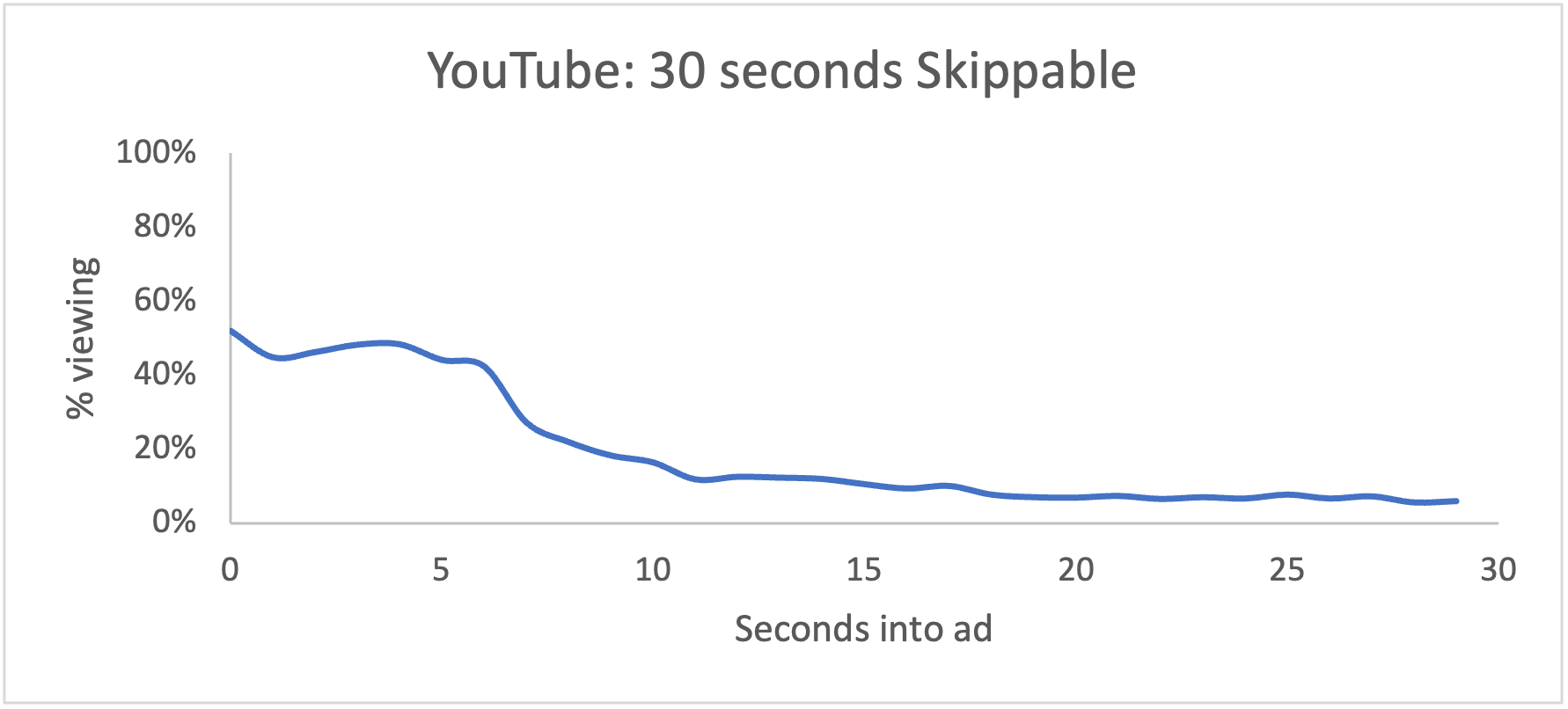

We can compare this to similar data from Lumen about how people watch YouTube ads. What we see here is that engagement with YouTube ads is akin to TV ads – until such time as you can skip the ad. In fact, the first five seconds of a YouTube ad get marginally more attention than TV ads, but very few people are watching second 29 or 30.

What this data suggests is that, even if people are watching your ad, they may not be watching in the way you want them to watch.

But as a wise man once said: “you can’t always get what you want, but if you try sometime, you just might find, you get what you need”.

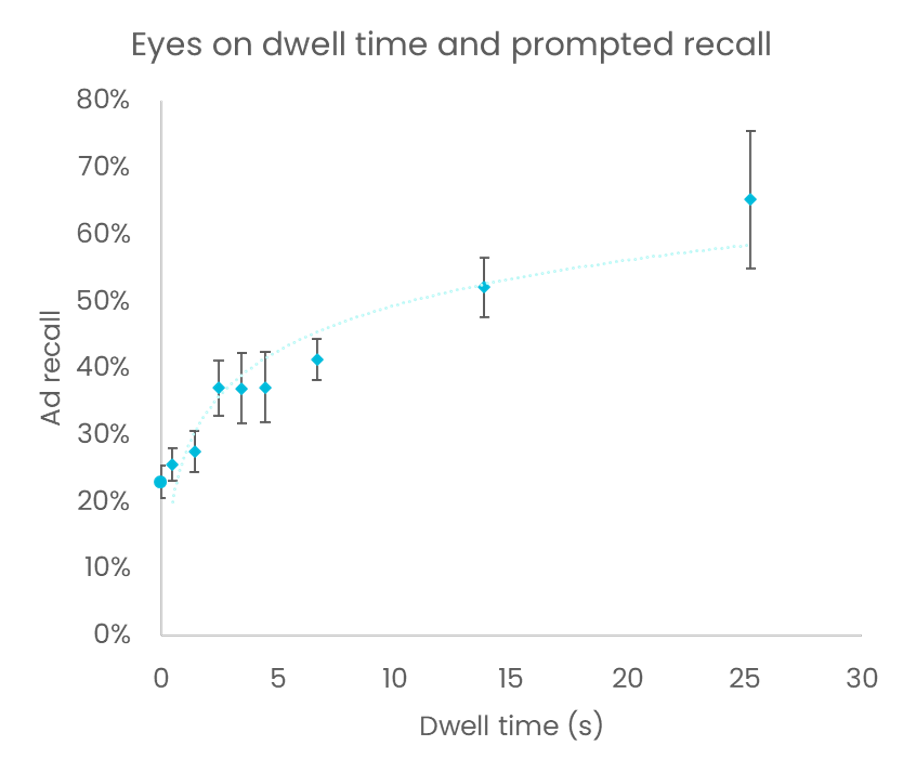

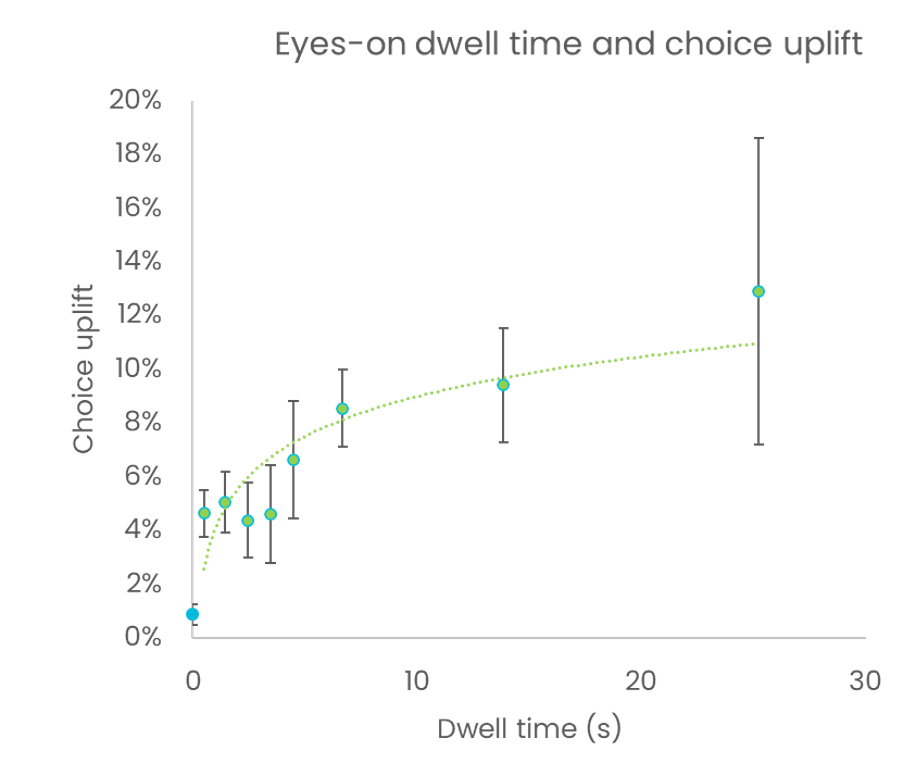

Because advertising does work – even in a short amount of time, or when people are distracted. Last year, Dentsu reported on the world’s largest advertising attention study, their Attention Economy project. This combined passive data collection from the Lumen panels with controlled tests which allowed us to assess the impact of attention to advertising on recall and ‘short term advertising strength’ – a questionnaire approach first developed by John Philip Jones in the 1990s to assess the impact of advertising on brand choice.

What these experiments showed was that while more attention is almost always a good thing, some attention is better than nothing. If we just look at the mobile results from the UK tests, we can see that the relationship between attention and recall/brand choice is non-linear, and that a little attention can go a long way.

What this suggests is that advertising can be – and often is – effective at building salience and directing desire, even in quite small amounts.

But if advertising works, then it works in a radically different way to the way we think it works.

This data suggests that most ads get glanced at rather than pored over. This raises questions about how we currently conceptualise reach curves or define what an ‘effective impression’ is.

The data suggests that these glances can trigger memories and desires – though the size of the error bars suggests that there is a big difference between impactful advertising and wallpaper. Ads with simple design and iconic imagery, that stand out from a busy environment, may make the most of the time available.

Finally, the data points to more sophisticated attribution models, that don’t assume that all media – or all creative – is created equal.

This understanding of how the world – and advertising – actually works is exciting and liberating. As Mick might say: sing it to me, baby.