00.00

4 Ages of Attention

Four ages of attention

Our understanding of attention to advertising has evolved significantly over the last ten years. But our deepening understanding is not merely down to the accretion of more data. Our mode of understanding has changed. It’s not just that we know more, but what we think is worth knowing has changed. Understanding the evolution in these ‘ways of knowing’ may help us make sense of where we are today, and what we can expect in the future.

It occurs to me that we have gone through four ‘ways of knowing’ over the last ten years:

-

An age of wonders, where attention researchers provided strange new perspectives that challenged our existing assumptions. These initial years were interested in highlighting PARADOXES.

-

A period of ‘truth to nature’, where attention specialists tried to make their data make sense to the lived experience of agencies and advertisers. This period was concerned with IDEAL TYPES of attention.

-

A period of performative objectivity, when, instead of trying to demonstrate consistent patterns in the data, we have become more interested in the inconsistencies and divergencies observed. These years have been all about having a BLIND EYE, and ‘letting the facts speak for themselves’.

-

A move towards ‘trained judgement’. Researchers now approach attention data not only in the spirit of learning, but on the spirit of doing. It is the RELATIONSHIPS between insight and action that constitute learning.

The sharp-eyed amongst you will notice that this schema draws heavily on Lorraine Daston and Peter Galison’s seminal book, Objectivity. Following their lead, what might we learn about the evolution of advertising attention studies?

The Age of Wonders

Back in 2013, when we first started Lumen, we’d begin most meetings with potential clients with some hardcore humiliation. ‘What if I were to tell you that most people ignore most of your advertising?’, I would begin. We’d show some initial data about quite how few ads actually get noticed, and for quite how short a time. There would be gasps, moans, anger even. ‘Why do we bother?’, clients would say. ‘All that effort – for 1.7 sec of actual attention!’

Joseph Wright of Derby, Experiment on a bird in an air pump (1768). Early scientists often felt the need to shock their publics into new ways of thinking

This was not just theatrics, but a necessary strategy. Any new science has to establish why it is worth the bother. It has to up-end established opinion, and point out scandalous paradoxes in the existing paradigm. Daston has shown that early modern scientists did the same thing. They would keep ‘cabinets of curiosities’, Wunderkammers stuffed with strange objects and monstrous creature. The aim was to destabilize people’s confidence that the way that they currently saw the world was the only way to see the world. This could be uncomfortable experience: not for nothing was the motto of the Enlightenment ‘Sapere Aude’ – ‘Dare to know’.

But the problem with being mischievous and audacious is that you create a problem without necessarily providing a solution. Sure, people don’t look at ads as much as we think they do: now what? Mark Twain once said that everyone talks about the weather, but no one does anything about it. The same could go for the paradoxes of smart-arsed attention researchers.

Truth-to-nature

The ‘so what?’ question led to creation not only of new tools, but new concepts to make sense of the newly discovered reality of attention. Not content simply to tear down the old way of thinking, we had to build up an alternative way of seeing the world.

At Lumen, we followed a strict naturalism. To be conquered, we claimed, nature must be obeyed. What are the ‘natural patterns’ of attention? What are the typical ‘shapes of attention’? How can we teach clients to go with the flow rather than kick against the pricks? We sought regular and predictable patterns in the data, things that we could hold on to and depend on in the face of our previously corrosive skepticism.

Interestingly, our mode of truth-to-nature sense making matches Daston and Galison’s descriptions of early ‘gentlemen scientists’ to a ‘t’. Responsible researchers of the eighteenth century did not see their role to simply present raw facts to their public. Instead, they would present an ideal type of a flower or a cloud or a process based on a synthesis of their intellectual labours. The job of the natural philosopher was to attend to variety of nature, and find the hidden unity lurking underneath. The process rhymes well with our time spent descrying the different ‘typologies of attention’ to advertising.

Objectivity

The problem with the ‘truth-to-nature’ approach is that your assumptions about ‘nature’ influence your description of the truth. You only see what you look for, and sometimes you can’t help imposing order when there is none to be found.

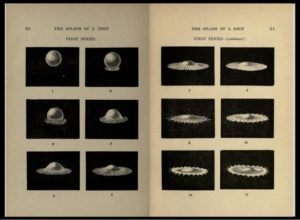

Daston and Galison tell the heartbreaking story of a man called Arthur Mason Worthington, who had spent a large part of his adult life trying to understand the shape made by milk drops when then splash. As a good ‘true-to-nature’ scientist, he boiled down his considerable learning into a series of beautiful, idealized diagrams of the process. But at the end of his career, he felt that he has wasted his life, not (just) because researching milk drops is an astonishing waste of time, but because of the way he had presented his data. Instead of interpreting his data via carefully considered hand-drawn images, he felt that he should have ‘let the facts speak for themselves’. The ‘blind eye’ of the photographic camera was what he should have been aiming for.

A.M Worthington, The Study of Splashes (1877-1895). Hand-drawn ‘ideal types’ of milk splashes, based on hundreds of photographic observations.

I have some sympathy – and not just because I have devoted a considerable portion of my life to something almost as absurd as milk splashes. The emphasis on the ‘so what?’ can blind you to the ‘what’. While there are patterns and regularities in the data we collect, there is great variation. Yes, we can predict the impact of size and time-in-view on attention to advertising – but attention to advertising is a function of creative, and context, and targeting as well. Where once we were afraid of the ‘scandal of inconsistency’ in our data, now we are more concerned about the ‘scandal of consistency’ – of data that follows a suspiciously regular character. Show me the data, warts and all!

Trained judgement

However, the fetishization of objectivity is just as much an act as the previous modes of knowing. You can’t not have a theory. The data don’t ‘speak for themselves’. The is no ‘blind eye’. To claim otherwise is philosophically naive, historically illiterate and factually untrue. The very units of measurement that we have developed to understand attention contain within them assumptions about what is worth investigating – and what is not. It’s all interpretation, all the way down.

What matters, we have found, is not so much what you collect but what you do with it. And this fourth ‘way of knowing’ is where we find ourselves today.

Daston and Galison show that modern scientists are less concerned with performative objectivity and more interested in acting in the world. They trust the data they use, but recognize it as just one window on the world – one that aids the judgement of the trained practitioner. What matters is how one symbolic system helps explain other symbolic systems to get stuff done. The pragmatism of CS Pierce and John Dewey lies at the heart of modern ‘ways of knowing’.

Charles Sanders Pierce (1839-1914), one of the founders of philosophic ‘pragmatism’.

Is it an accident, then, that Lumen has adopted this more ‘pragmatic’ approach since we started working alongside Ezra Pierce, a scion of the same family as the famous philosopher? In partnering with Ezra’s company, Avocet, we have been able to link our attention predictions to their ad tech stack. This has allowed us to run thousands of experiments, showing how attention to a particular campaign leads to clicks, or sales, or (thanks to our chums at OnDevice Research) brand recall for that particular campaign. Rather than having one big theory based on one accepted truth, we have lots of little theories based on the interaction of disparate datasets.

This a profound change in what constitutes knowledge about attention to advertising. Up until now, we have been measuring things. Now we are using attention data to understand relationships. We have come to understand that what we are trying to explain is a process. Ads are as much events in time as they are objects in space.

Where next?

Daston and Galison would be quick to point out their ‘ways of knowing’ can overlap and coexist. Nor do they make value judgements about the different modes of understanding. Theirs is a description of what is, rather a prescription of what ought to be. But I can’t help but think that the pragmatic search for relationships between datasets is a better way of understanding the problem of advertising, at the very least. We will never ‘solve’ attention, or advertising. The eye, like the heart, has its reasons that reason knows not. But we can learn more by acting in the world than by merely observing it.

Over the last ten years, we have developed the tools – both technological and conceptual – to create a deeper understanding of how advertising works, and how it would work better. As an industry, our knowledge will grow, with more data, but also more metaphors and models, used to make sense of ourselves and our industry. But it will be learning through doing that will give us a new mode of understanding.

Where next?

Daston and Galison would be quick to point out their ‘ways of knowing’ can overlap and coexist. Nor do they make value judgements about the different modes of understanding. Theirs is a description of what is, rather a prescription of what ought to be. But I can’t help but think that the pragmatic search for relationships between datasets is a better way of understanding the problem of advertising, at the very least. We will never ‘solve’ attention, or advertising. The eye, like the heart, has its reasons that reason knows not. But we can learn more by acting in the world than by merely observing it.

Over the last ten years, we have developed the tools – both technological and conceptual – to create a deeper understanding of how advertising works, and how it would work better. As an industry, our knowledge will grow, with more data, but also more metaphors and models, used to make sense of ourselves and our industry. But it will be learning through doing that will give us a new mode of understanding.

00.00